Fatima Shahzad

On June 9, 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution, Eric J. Hobsbawm was born and he went on to contribute more to the study of the 20th century than perhaps any other historian. The main feature of his writings that set him apart from other historians was the fact that he did not feign neutrality and wrote of the subject matter from his own socio-political perspective. A lifelong Marxist, he brought a new approach to writing history, and became one of the most renowned labour historians and explored topics such as industrialization, working class struggles and nationalism among others. To those with an interest in history, there is much to learn from his work which remains as relevant to our times as it were to his own.

A short biography

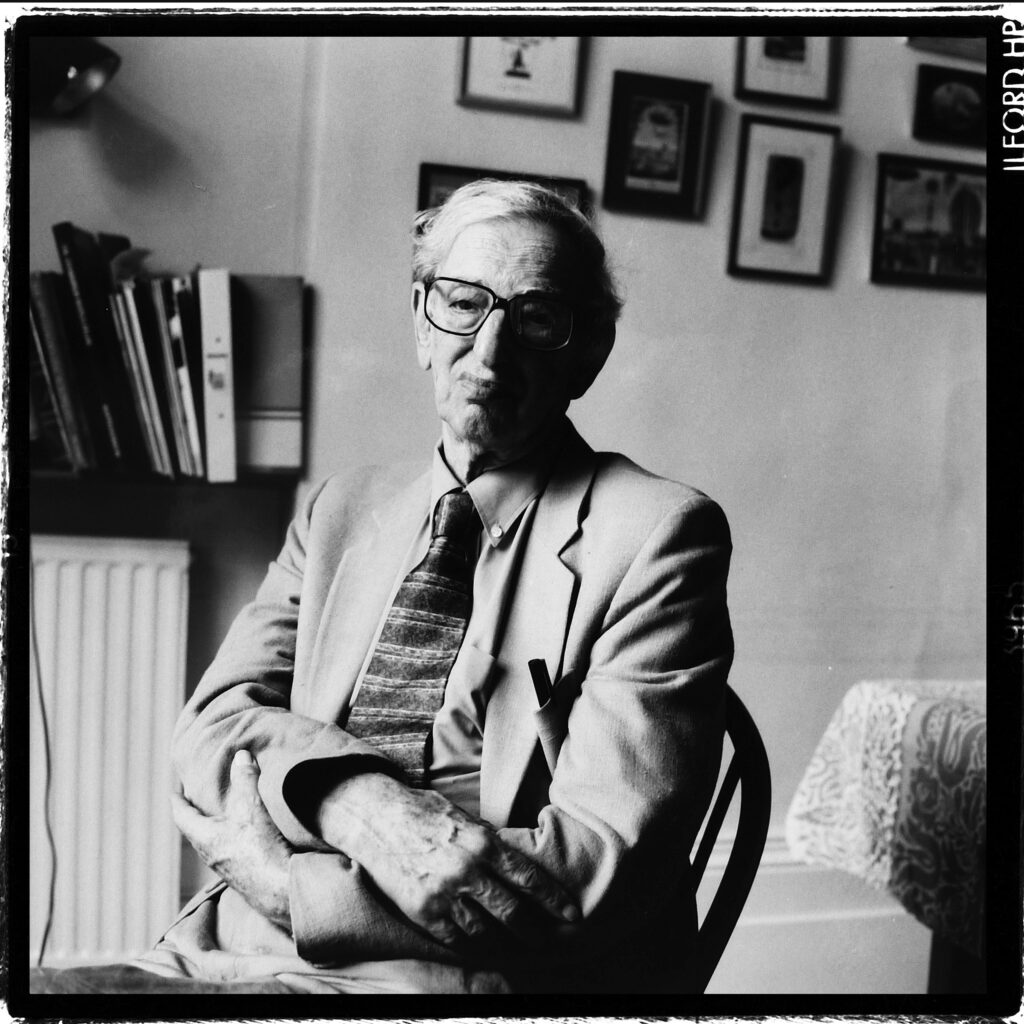

In order to understand Hobsbawm, one must look at the events of his life. Born in Egypt due to his British-born father’s occupation as a merchant, he later moved to Vienna before going to college in London. He developed sympathies to leftist thought in his youth and ended up joining the British Communist Party in 1936. He opted for a career in teaching economic and social history at King’s College, Birkbeck College and the University of London, as well as writing articles and essays for a range of different publications. At a time when his hopes of proletarian revolution seemed dampened, he travelled to Latin America during the 1960s, only to have them revived and alter his self admittedly Eurocentric scope of history. Before his death in 2012, at the age of 95, spanning most of the 20th century as well as the dawn of the war on terror, he also wrote of globalization, culture and terrorism with much insight to offer. It is obviously not possible to delve into the full depth of his views here, except for a brief overview, which may prove to get the reader to take that task upon themselves.

On industrialization

Hobsbawm explained the cause of the Industrial Revolution: the impact of industrialization on the standard of living, the changing nature of labour relations and struggles throughout the history of the modern world, most notably in his industry and empire. Here he challenges the mainstream assumptions such as dismissing the Industrial Revolution as a mere historic accident, alluding to the spirit of Protestantism (by pointing out that many regions ate the forefront of industrialization were indeed Catholic) or even British supremacy.

He talks about the material conditions and mechanisms which may have been effective in producing such a change. He does this by first designating the Industrial Revolution as a capitalist one, which it doesn’t necessarily have to be (as recent history in many underdeveloped countries has shown). As capitalism requires unending growth, the particular rate of industrialization seen in Britain was thus fuelled by developing new markets abroad to expand trade via colonization, in effect slowing down, if not completely destroying the natural development of the colonized regions.

He also goes on to contend with the real effects of industrialization in the life of an average worker and why the changes seen in mortality, population growth, and wages among other measures occurred. On population growth he emphasizes the role of the demand for child labour which accounts for rapidly increasing birth rates throughout that whole time period, as well as the dependence upon employers to sustain life. He also points out, with much evidence statistics and detail, many of the weaknesses and flaws in the metrics used to measure the standard of living, which are then used to draw conclusions about rapid improvement that is so commonly associated with this time period. In his collection of essays entitled Labouring Men, Hobsbawm follows the early working class movements arising from this conflict, from the Chartists to the Methodists as well as broader labour traditions.

Communist history

In the opening essay of his book Revolutionaries, entitled The Problems of Communist History, he states, “Each communist party was the child of the marriage of two ill-assorted partners, a national left and the October Revolution. This marriage was based on both love and convenience,” referring to the fact that every Communist party that existed after the Russian revolution followed a Bolshevik line to some extent, especially since other forms of socialism, next to its triumph, seemed insignificant in producing revolution. He later discusses the Stalinist era and the nationalist tendency which surfaced as a result within socialist parties.

It is made even more interesting due to the fact that much of it is an expression of his own thought and sentiments regarding these movements, as someone who was sympathetic to the cause and also sought to explain and analyse it. In the same book he reflects upon Latin American socialism, particularly guerrilla warfare, Vietnam and the Cuban revolution, as well as reflecting upon the significance of other forms of socialism, such as anarchism and the Spanish Civil War. He also has much to say about the nature of various working class movements and reasons for the failure of revolutions in many European countries such as France, Britain, Germany and Italy. Exploring history from a Marxist lens isn’t limited to any one of his works. In his famous Age of Extremes, he goes over the entire communist current from 1914 until 1991.

Legacy

Today Hobsbawm may be known to us as the “Communist who explained history,” but he was never really an activist in his lifetime and was sometimes critiqued by active communists for writing for bourgeois publications and institutions. However, the awareness and insight he helped generate in the service of not only understanding but supporting socialism cannot be overlooked either. He was ironically deemed a Stalinist at times by pro-capitalist thinkers. But what can we learn from his life and work?

When it comes to writing history in a distinct and original manner, there are hardly any writers whose work possesses such a strong character as Hobsbawm’s. He put this information across a vast breadth of time, most notably in his three volumes Age of Capital, Age of Empire, Age of Extremes. Eric Hobsbawm perhaps most notably challenged the view that neutrality is the same as objectivity, a notion all too common in our academic institutions’ approach towards teaching history. Neutrality mostly favors a centrist narrative, often that of the establishment, limited to a powerful minorities’ interest, and thus isn’t remotely close in presenting the reality for the vast majority of people.

For students of history it is essential to be familiar with his work and remember to explore such topics which are in much need of research in Pakistan, and of reaching often bold and radical conclusions which may deviate from the generally acceptable ones. To not discount personal experiences and views, but to be active members of movements in which you believe in, and write as to be true to yourself and the world as you see it.

The Students’ Herald News Desk focuses on reporting the latest news regarding student politics and campus updates to you.

The News Desk can be reached at admin@thestudentsherald.com